Gambling harm is a co-created phenomenon. The institutional, structural, and technological arrangements, which make up this phenomenon, requires meaningful reform (Roberts, 2021). There is an urgent need for public health policy development led by our elected government, in consultation with those with lived experiences of gambling harms, and not led by vested commercial interests.

To address gambling harms there needs to be a shift in perspective from the current policy of “Responsible Gambling” which blames and victimises people affected by gambling harms. It is a policy with primary focus upon individual pathology and individual behaviours. It is a policy which research has demonstrated doesn’t work and is rejected by those with lived experience of gambling harms (Roberts, 2021).

We need to look beyond individual pathology, towards examining gambling behaviour within the context of manufactured gambling products, designed environments, historical business models and institutional arrangements which co-create the phenomenon of gambling harms (Roberts, 2021).

The current debate over the cashless gambling card for poker machine use is not new (refer Livingstone, SMH 22/12/22). A smartcard (cashless gambling card) was a key recommendation of the Productivity Commission Report 2010 to give poker machine users a consumer protection tool, within current arrangements for the provision of poker machines in the community. This is particularly important given Australia has 20% of the fastest, most voracious machines, with 50% of them here in NSW. It is noted that in the UK such machines are only available in Casinos, yet here in NSW they can be found in virtually every pub and community club.

Whilst this current debate has been initiated by the NSW Crimes Commission to combat money laundering, the introduction of this technology, will create increased transparency and equity for product users and increase consumer protection for all people engaging with a recognised “product of dangerous consumption”. As with cars and their technological safety measures (seat belts), the cashless gambling card will be a technological tool for increasing safety measures for all poker machine users.

It is well recognised that technology-based systems can support people who gamble to limit their spending and are “effective not only in preventing the escalation of gambling problems but also, over time, in reducing the harm for gamblers who are already chronically overspending” (Rintoul & Thomas, 2017 as cited in Roberts, 2021:336).

A cashless gambling card, with the functionality and precautions as recommended by the Alliance for Gambling Reform (see below), will create a more equitable playing field for consumers with transaction transparency, which will protect the misuse of the product for money laundering and at the same time increase consumer information in real time. It will apply an effective public health strategy already in use in other jurisdictions (Norway) and committed to in Australia (Tasmania).

The Cashless Gambling Card has much to recommend it. From the point of view of people who have experienced gambling harms, the card will meet the need for preventing money laundering, whilst at the same time assisting to reduce and prevent gambling harms and the negative impacts on individuals, families, and communities.

Recommendations for a Cashless Gambling Card:

As foundation members of the Alliance for Gambling Reform the Gambling Impact Society (NSW) supports the following recommendations from the AGR Position Paper (Jan., 2023) refer https://www.agr.org.au/_files/ugd/f3b93a_bfcb93c5014a4d849de69db27979fb40.pdf

- To achieve harm minimisation and address criminal activity relating to EGMs (electronic gaming machines), all Australian jurisdictions should urgently introduce a requirement for mandatory, registered cashless gambling cards for use with EGMs in all venues.

- The system must be administered centrally in each jurisdiction, by the appropriate regulatory authority.

- Any individual may hold only one card, and the card holder’s identification must be verified at the point of registration.

- The card must have pre-commitment functionality (i.e. set maximum loss limits), and pre-commitment must be mandatory for all users. Once the set limit is reached, the card holder cannot continue to use an EGM.

- The card system should include default maximum loss limits for all users (concurrent daily, monthly and annual limits should be trialled).

- Users must be able to voluntarily reduce their pre- commitment levels to less than these default maximum limits, with immediate effect.

- Careful measures should be trialled for users with demonstrated financial capacity and no history of gambling harm, to enable some increase of pre-commitment beyond the default maximum loss limits.

- Card functionality should enable the setting of play limits, including requirements for breaks in play, and maximum play periods.

- Card functionality should also link to self and third-party exclusion registers, enabling prevention of gambling by excluded persons.

- The card holder may only load funds onto the card using cash or an EFTPOS card, not a credit card, and automated top-ups must be prohibited.

- The cashless gambling card must not be linked to any loyalty scheme or other incentive scheme.

- The card should generate data accessible to the card holder, including time spent using EGMs, and money lost or won.

- De-identified data from the card system should be available to relevant jurisdictional authorities to support monitoring, review, and ongoing policy and program development; and bona fide researchers should be able to request de-identified data from the system for research that seeks to support harm minimisation.

- Jurisdictions should collaborate to achieve consistency and best practice with the design and implementation of the system, noting that implementation issues may include timeframes, costs, and training requirements for venue staff.

Background Research:

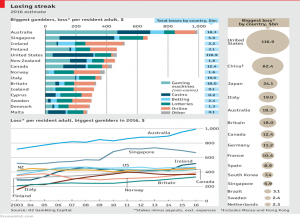

- Australia is one of the biggest gambling nations, ranking fifth for gambling losses overall but first for individual resident losses (As Young and Markham (2017:1) note: “Losses by Australians on pokies outside of casinos dwarf those of any other comparable country. They are 2.4 times greater than those of our nearest rival, Italy”. (Roberts 2021:30)

- Australians lose over $25 billion each year on a range of gambling products, and at least half of these losses are through poker machines. (QGSO 2021)

- Approximately $95 billion in cash flows through poker machines in pubs and clubs in NSW each year, making it the gambling capital of Australia. (NSW Crimes Commission, 2022)

- It is estimated that Australia has one poker machine for every 114 people, and more per person than any country in the world, excluding casino-tourism destinations like Macau and Monaco (Young & Markham, 2017:1) – as cited in Roberts 2021:45.

- The total value of money estimated to be laundered through pokies in NSW is $20 billion. (NSW Crimes Commission, 2022)

- In NSW, $23 million is lost every day through pokies in pubs and clubs; in Victoria, the figure is $8.4 million per day, and in Queensland, $9 million. (AGR, 2023)

- Liquor & Gaming NSW estimates that 22 per cent of EGMs in NSW have load‐up limits of $5,000, 56 per cent have load‐up limits of $7,500, and 22 per cent have a load‐up limits of $10,000 thanks to grandfathering provisions (Financial Times Review, 26/10/22)

- The social costs of gambling – including adverse financial impacts, emotional and psychological costs, relationship and family impacts, and productivity loss and work impacts were estimated in to be 4.7 billion annually (Productivity Commission, 2020).

- Estimates of social costs gambling harms have been revised since 2010, to around $7 billion in Victoria alone (Browne et al. 2017).

- Gambling-related harms affect not only the people directly involved, but also their families, peers and the wider community (Goodwin et al. 2017).

- 85% of the aggregate community harms from gambling are generated by people who do not meet the clinical criteria of a “problem gambling e. people who are low/moderate risk for problem gambling are still experiencing significant harms (Browne et al, 2016)

- Since 2001 we have known that 50% of people who gamble once a week or more on poker machines will experience some level of gambling problems (Dickerson. 2003).

- Significant harms from poker machines have been identified for over 20 years in Australia (Productivity Commission 1999, Productivity Commission 2010, Roberts, 2021).

- The design of poker machines including specific features such as Losses disguised as Wins, Near Misses. The sensory and relational aspects of this have been implicated as major factors in why harms are so prevalent amongst regular users of EGMS (pokies (Armstrong, 2017; Barton et al., 2017; Dickerson, 2003; Harrigan & Dixon, 2009; Murch et al., 2017; Livingstone & Woolley, 2007; Livingstone et al., 2008; Lole et al., 2015; Schottler, 2019; Schull 2012) – as cited in Roberts, 2021:74.

- Research studies suggest that game features and algorithms built into poker machines are specifically designed to encourage continuous play and thereby reinforce behaviour to such a level that it becomes detrimental to the product user (Dixon et al., 2010; Harrigan and Dixon, 2009; Schull, 2006). Poker machine design features, speed of play, cost of play and the interaction with human psychology have been implicated (Barton et al., 2017; Harrigan et al., 2015; Lole, 2014; Parke et al., 2016; Rockloff & Hing, 2013) in the direct relationship between the extent of gambling harms and this specific product – as cited in Roberts, 2021:74.

- From a public health perspective, gambling is considered an industry of dangerous consumption-generating harms externalised into the community and in need of reform (Adams, 2005; Livingstone & Woolley, 2007; Orford, 2009; Thomas, et al, 2017) – as cited in Roberts, 2021:45.

(Click to enlarge)

Figure 2: The Economist Chart of the Day. Reprinted from “The World’s Biggest Gamblers: Australia was the first country to deregulate gambling, and it shows” (2017, Feb 7), The Economist.

Submitted by:

Dr. Kate Roberts

Executive Officer

Gambling Impact Society NSW

0401370042 m

References:

Browne, M., Langham, E., Rawat, V., Greer, N., Li, E., Rose, J., Rockloff, M., Donaldson, P., Thorne, H., Goodwin, B., Bryden, G. & Best, T. (2016). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: a public health perspective Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Browne M, Greer N, Armstrong T, Doran C, Kinchin I, Langham E & Rockloff M 2017. The social cost of gambling to Victoria- external site opens in new window. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Dickerson, M. G. (2003). Exploring the limits of “responsible gambling”: Harm minimization or consumer protection? Gambling Research Journal of the National Association for Gambling Studies Australia, 15, 29-44.

Goodwin BC, Browne M, Rockloff M & Rose J 2017. A typical problem gambler affects six others. Journal of Gambling Studies 17(2):276–89.

Livingstone, C. 2022. Cashless pokies will work with precommitment don’t muddy the debate Chris Minns, SMH, Opinion. December 22,

Linhttps://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/cashless-pokies-will-work-with-pre-commitment-don-t-muddy-the-debate-chris-minns-20221216-p5c6xy.html

Financial Times 26/10/22 https://www.afr.com/chanticleer/why-a-pokie-crackdown-will-have-pub-owners-nervous-20221026-p5bt48

NSW Crimes Commission 2022 https://www.crimecommission.nsw.gov.au/final-islington-report.pdf

Productivity Commission. (1999a). Australia’s Gambling Industries. Report No. 10. AusInfo, Canberra.

Productivity Commission. (1999b). Australia’s Gambling Industries: Draft Report, Commonwealth of Australia.

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling. Report No. 50. Commonwealth of Australia.

QGSO (Queensland Government Statistician’s Office), Queensland Treasury 2021. Australian gambling statistics, 36th edition, 1993–94 to 2018–19.

Roberts, K, 2021, Welcome to Clubland: Exploring sociomaterial dimensions of poker-machine gambling harms in community-clubs in New South Wales Australia. Thesis University of Wollongong, https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1/1378/